Introduction

In his recent article, Allen Wu shared with us some lessons that he had learned by playing other games. The following part really resonated with me:

“I like to think of playing different games as weight training. Most turn-based strategy games feature the same high-level mechanics: asymmetric information, tempo, understanding uncertainty, and so on.”

“However, just like different exercises target different muscles, these components matter more or less in different games. Bluffing, for example, is a minor component in Magic, but a major component in poker. Studying poker for a week will give you a better and more complete understanding of bluffing than playing Magic for a year.”

The first time I realized this was a couple of months after Hearthstone came out, when I had been playing the game for unhealthy amounts within a short period of time. The Hearthstone decks are relatively small, only 30 cards, and some of the matchups often went very long. This meant that I frequently found myself in situations where the odds of drawing a specific card were significantly higher than they usually are in Magic. Thus, I was thinking about my possible draws and their impacts on my decisions much more often than I ever did in Magic.

Shortly thereafter I was watching some of Luis Scott-Vargas’s Cube Draft videos, and I noticed that he was doing specifically those kinds of calculations in Magic. He made plays that might have been slightly suboptimal if you only look at the cards in his hand and on the battlefield, but put him in a position where if he drew some specific card, he would be in a much better position to take advantage of that. And being Luis, he obviously drew those cards more often than statistics should allow.

This lesson really stuck with me and I learned to look for opportunities where I could give myself the chance to get lucky without losing much if I didn’t.

In the past year, I have been playing a lot of chess. I had fun watching the PogChamps event, where a bunch of popular streamers got coaching from chess masters to get started, and then competed in a tournament against each other.

Whenever the coaches gave tips to the students about chess strategies, I almost always found a way to translate them into Magic terms. So in today’s article, I’m going to tell you how understanding some of the fundamental principles of chess can help you become a better Magic player.

《Knight Errant》

A very common advice for chess openings is to develop your knights before your bishops. Like the 7th edition version of 《Knight Errant》, your knights in chess should be quick to charge into battle. There are exceptions, of course, but the underlying reason why your knights should move first is that you should develop with flexibility.

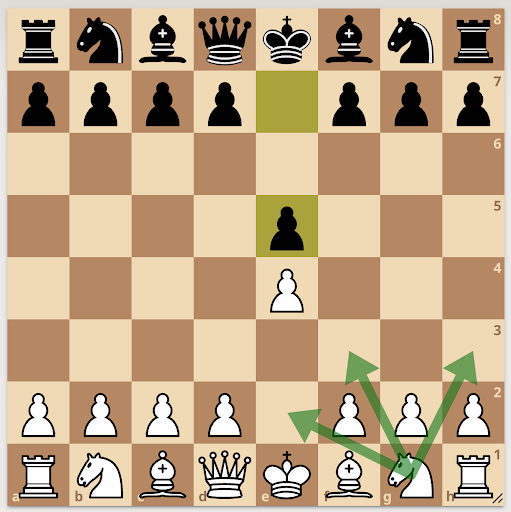

Let’s look at the classic E4-E5 opening as an example:

While your king’s knight technically has three possible squares it can go to, one of those squares is a much better place for it than the other two. You want your knight to be as active and centered as possible, so you really want it to be on the F3 square. On the other hand, if you look at the F-file bishop, it has five different squares it can go to, and E2, D3, C4 and B5 are all common choices depending on what your opponent does. You don’t want to waste time by moving your pieces twice, so you first want to see how your opponent responds before deciding where to place your light-squared bishop.

Sometimes developing with flexibility in Magic can be very simple, like first-picking a colorless card over a more powerful multicolor card in a draft. Or if you plan on casting a card draw spell on your turn, you should do it first in case the cards you draw change what you want to do with the rest of your turn. Playing your draw spell last is a mistake I’ve seen players make more times than I can count, and which I have done myself more than I’d care to admit.

As a more advanced example, let’s say that you’re on turn 4 of a Magic game, with 4 lands in play, and your hand is an assortment of cards that cost 2, 3 and 4 mana. What do you play?

A very common mistake that I see is players using both of their 2-cost cards, because it maximizes the value gained on the current turn. But I would argue that in spots like this, you should most of the time try to develop with flexibility.

Whenever possible, I try to play the most expensive cards first and save the cheaper ones for later. This order of sequencing lets me have more flexibility later. Maybe I draw a land and I want to cast a 2-cost card and a 3-cost card next turn. Maybe I draw another 2-cost card and I’ll have a better double-spelling turn by casting the freshly drawn 2-cost card with one of the earlier ones, instead of casting the two I already had. There are many ways in which your draw steps and your opponents’ plays could affect what you want to do, and more often than not, casting your expensive spells first leaves you in a more flexible position.

As another example, let’s say that your opponent plays a creature and you have two answers in hand – an 《Exclude》 and a 《Cast Down》. Which one do you use? For me the answer is easy, because if drawing a card and getting a 2-for-1 is wrong, I don’t want to be right. But if you have some amount of self-discipline, you should first ask yourself which of the options leaves you more flexible later.

Which one of them it is, though, depends on the circumstances. Sometimes your opponent has a bunch of legendary creatures in their deck and you would rather spend the unreliable 《Cast Down》 first. Other times it’s important to cast the 《Exclude》 first, because flexibility means having the option to tap out on the following turns instead of holding up mana for a counterspell. The answer will vary from situation to situation, but as long as you remember to ask the right questions, you have a good shot of finding the right answers as well.

《Choking Tethers》

When you’re playing against a chess engine, you will quickly notice one of two things: either the game is already over because the engine used some black magic to eat all of your pieces, or you’re looking at the board in desperation, trying to find a good move for yourself on a board where none are available.

The latter is a thing that engines are much better at than humans, and that the absolute best engines do even better than the merely superhuman ones. They make a sequence of moves which look harmless on the surface, because their purpose is not to directly attack you. Instead, they slowly suffocate you to submission by seizing control of all the squares that your pieces could go to, building the pressure little by little until you wish that you were playing a game with more variance.

Humans can, of course, sometimes succeed in the same when playing against each other. A good example of this is a game played between Lev Psakhis and Mark Hebden in the 1983 World Junior Championships. They ended up in the following board position:

If you look at it carefully, the player with the black pieces is completely paralyzed and can’t make any useful moves. As a result, the player with the white pieces has all the time in the world to do what he wants, and the game was eventually decided by the white king walking from the bottom right corner of the board to the top left corner of the board to help promote their pawns.

As humans, we have a tendency to focus on our own cards and advancing our own game plan, even when it would be more effective to try to obstruct theirs.

If you want to see a great example of how to apply this to Magic, I recommend checking out my earlier article called “Controlling the Flow of the Game”, where I analyze a game between Lee Shi Tian and Ivan Floch. In that game, the Hall of Famer from Hong Kong simply robs the Slovakian Superstar of opportunities to use his cards effectively.

Another frequently occurring situation is when you have a choice between advancing your own development by drawing more cards or deploying more mana, or preventing the opponent from doing the same.

As a simple example, let’s say you’re playing Izzet Dragons against Temur Treasures in Standard. On your second turn, you have a choice between casting a 《Smoldering Egg》 to advance your own game plan, or a 《Burning Hands》 on the opponents 《Magda, Brazen Outlaw》.

In a matchup like this, I would lean towards stunting the opponents development over furthering your own. The easiest way to lose is to let the Temur player do what they want and cast 《Esika’s Chariot》 into 《Goldspan Dragon》 ahead of schedule.

As a more complicated example, let’s say that you’re playing Rakdos Arcanist in Historic against Jeskai Control. They have a 《Teferi, Hero of Dominaria》 in play with two loyalty counters, and a 《Narset, Parter of Veils》 as the last card in their hand. You have a 《Dreadhorde Arcanist》 in your graveyard.

You know that you’re going to cast a 《Kolaghan’s Command》 this turn, and that the first priority is to deal 2 damage to their 《Teferi, Hero of Dominaria》. That part is easy! But what should the second mode be? Should you bring back your 《Dreadhorde Arcanist》 or make them discard their 《Narset, Parter of Veils》?

The answer, again, depends. The question you should ask yourself this time is this:

Whom is the extra action more valuable for?

If they have a flipped 《Search for Azcanta》 in play and can spend their mana activating that instead of casting the 《Narset, Parter of Veils》, making them discard doesn’t meaningfully restrict their options. However, if they are out of gas and have to rely on drawing action off the top of their deck, getting rid of that 《Narset, Parter of Veils》 would be very valuable.

On the other hand, if you don’t have any other action left yourself, it seems very appealing to take the 《Dreadhorde Arcanist》 and hope that it can take over the game. But if instead of the 《Dreadhorde Arcanist》 you could just cast a 《Lurrus of the Dream-Den》 bringing back 《Dragon’s Rage Channeler》, and still have a couple of business spells left in your hand, taking the 《Dreadhorde Arcanist》 is not exactly on top of the priority list.

《Balance of Power》

A famous rule of thumb in chess is that pawns are worth 1 point, knights and bishops are worth 3 points, rooks 5 points and the queen worth 9 points. So when you trade a knight for a bishop, in theory you trade 3 points worth of material for 3 points worth of material.

But in practice, a lot of trades that would be equal points-wise aren’t actually all that equal, and positions where one side is up on material can still be less likely to win the game, if their valuable pieces are poorly positioned. If positional factors and material are in balance, the situation in chess is called

Translated to Magic terms, putting your opponent to a low life total can significantly reduce their options and force them to use their cards ineffectively. Sometimes a control deck has to spend a 《Wrath of God》 on a 《Noble Hierarch》 because they are at 1 life and can’t afford to take a single hit from the meek human druid. Dynamic factors can effectively lead to virtual (or even tangible) card advantage.

As an extreme example, there’s a phenomenon that some of my friends like to call by the name “aggro 《Moat》“. In essence, when you put your opponent to a low enough life total, they can’t ever attack you, because a counter-attack with all of your creatures would deal lethal damage. It doesn’t matter if all of their creatures are better than all of yours, they still can’t attack.

And if you have a couple of cards in your hand, your opponent doesn’t know whether they are useless lands or tricks that change the combat math. This makes the counter-attack often seem scarier than it really is, giving you even more time to draw your outs – assuming that you have some, of course.

As another example, the value of creature bombs in Limited changes wildly between different decks. A deck that can put on a decent amount of pressure can force the opponent to use their removal spells on other creatures, and then play a good-but-not-amazing card like 《Shimmerwing Chimera》 to generate enough value to win the game.

On the other hand, a slower deck might have a stronger bomb, like 《Archon of Sun’s Grace》, but it will instantly die to a removal spell because the opponent hadn’t had a compelling reason to spend theirs on anything else, and thus could afford to hold it for the target that mattered the most.

As a result, one of the best ways of beating a Limited deck with stronger cards is to put on some pressure to force them to use their cards suboptimally. In other words, you should aim for dynamic equality. This doesn’t mean you have to be a balls-to-the-walls aggro deck with stuff like 《Slither Blade》 and 《Battlefield Raptor》, as your pool of cards might not have the requisite cards for an extreme transformation like that.

I feel like aggression in Limited is often misunderstood. Many players seem to think that drafting an aggressive deck in Limited means making your curve as cheap as possible, and playing weak cards over more impactful, more expensive cards. In my experience, a good 5-drop is often better at pressuring the opponent than an uninspiring 2-drop, especially in Sealed.

In fact, my personal favorites to sideboard in against slower but stronger decks are slightly overcosted fliers. Playing overcosted cards doesn’t sound like a very aggressive idea, but in a relatively slow matchup being hard to block pressures the opponent in a much more meaningful way than a 《Lava Spike》 stapled onto a chump-blocker. Against other aggressively-slanted midrange decks those cards are garbage, but against slower decks you care more about the effect than the cost.

《Threaten》 vs. 《Execute》

There’s a famous saying in chess that “the threat is stronger than its execution”, which describes the dynamics of many control mirrors very well. Good examples of this are 《Wilderness Reclamation》 in Temur Reclamation mirrors in Standard (back when it was legal), and 《Teferi, Hero of Dominaria》 in Jeskai Control mirrors in Historic.

Back in Temur Reclamation’s heyday, I saw multiple players advocating for cutting all of the 《Wilderness Reclamation》 during sideboarding, transforming the deck into one that functions completely on instant speed.

The plan was to win with flash threats like 《Nightpack Ambusher》, 《Shark Typhoon》, 《Commence the Endgame》 and 《Brazen Borrower》, and never tap out.

The logic behind cutting all the Reclamations is that when both players are playing a draw-go flash game, resolving 4 mana sorceries is hard. The problem, however, is that if your opponent knows what you’re up to, you become exploitable.

Why is a 4 mana sorcery bad in the matchup? Control mirrors are often games of chicken where the one who tries to resolve their haymakers first gets theirs countered, and then the other player can untap and safely resolve their own. Reclamation mirrors were no different – the thing that punished you the most for trying to resolve a 《Wilderness Reclamation》 was them countering yours and managing to stick their own, resulting in an insurmountable mana advantage for the rest of the game.

When you cut all of your 《Wilderness Reclamation》, you lose the ability to punish the opponent for tapping out. This gives the opponent significantly more freedom in choosing how and when to cast their spells. They can force some action during your end step, and then untap and tap out for a big 《Expansion/Explosion》, or stick an 《Uro, Titan of Nature’s Wrath》, knowing that you can’t do anything that they would actually lose to.

But if they keep their 《Wilderness Reclamation》 in, you don’t have the same freedom. Tapping out is a big risk.

Also, sometimes you just don’t have the answer. Maybe you didn’t draw any, or they already depleted your limited supply. Regardless, they gain a decent amount of percentage points in a matchup by doing the most powerful thing possible, and 《Wilderness Reclamation》 + 《Expansion/Explosion》 is certainly quite a bit stronger than casting 《Nightpack Ambusher》.

The same thing applies to 《Teferi, Hero of Dominaria》 in Historic Jeskai Control mirrors. It’s great in game 1s, as both players have a very small amount of hard counters. You’re often rewarded for just jamming it and hoping that it resolves. If it gets 《Memory Lapse》, you might have lost a bit of tempo, but you still get to do the same thing again next turn.

When we were preparing for the Challenger Gauntlet, our team had a discussion about how many copies of 《Teferi, Hero of Dominaria》 to side out in the mirror matches, which was by far the most popular matchup at the tournament.

The tournament had open decklists, and our matches were streamed, so we thought that we couldn’t afford to board out more than 1 of the 3 planeswalkers, even though it’s hard to resolve against the cluster of 《Dovin’s Veto》 and 《Mystical Dispute》 that the opponents would be bringing in.

The reasoning for this was exactly the same as explained above – if we went down to 0 or 1 copies of the card, the opponents wouldn’t have to respect it anymore, and with the matches being streamed they would very likely know what we were up to.

For the poker players out there, you can also see similarities between this and the exploitative vs. game theory optimal play style discourse. Against weaker opponents you can spot tendencies like them being risk averse and avoiding tapping out at all cost, and against those opponents you can adjust your play style to exploit the fact by boarding out all of your 《Teferi, Hero of Dominaria》 and 《Wilderness Reclamation》.

But against great opponents, the best strategy is the GTO strategy that can’t be exploited by others, which leads to a mixed strategy that forces your opponent to respect your range – meaning boarding out only some of your expensive but powerful sorcery speed effects, but not all of them.

《Future Sight》

About two months ago I was watching Crokeyz preparing for the PogChamps chess tournament. He was analyzing one of his matches afterwards, and was baffled why a pawn move from e7 to e5 changed the evaluation by a full point in favor of the opponent. The computer’s preferred move was a similar but more patient e7 to e6.

To a beginner this must have seemed very counterintuitive. Pushing the pawn further came with tempo, as it kicked out the opponent’s knight from an ideal square in the middle of the board, and there was no immediate threat visible that could pressure his central pawns.

The problem with the move was that it created what is called a backwards pawn – a pawn that can’t be protected by other pawns. This resulted in a long-term liability. Even if there weren’t any immediate threats to it, the weakness of the d-pawn would be hard, if not impossible, to fix.

This ability to see how the games will or could play out is an extremely important one. Well-known chess YouTuber Levy Rozman, a.k.a. GothamChess, has a popular series of videos where his subscribers send him replays of their games, and he tries to guess the ratings of the players based on how well they played. Probably the most telling sign of a player’s rating is whether their actions indicate having some kind of a plan or not.

The lowest rated players consistently make useless moves like attacking a piece that will simply dodge the attack and move to a better square than the one it ran away from, or they leave unprotected pieces hanging, or lose them to simple tricks and tactics. The intermediate players, on the other hand, start making moves with a purpose, like developing with flexibility.

The advanced players go even further than that. They recognize what their opponent is planning and trying to do, and then guard the squares to which the opponent would like to place their pieces. They also understand when their game plan requires a sacrifice or a downgrading exchange like trading a rook for a knight, because they value the pieces by how important they are for enacting the plan, rather than some rule of thumb that usually provides the right answer. In other words, their piece evaluation is dynamic rather than static.

So to conclude, I would summarize many of the above lessons with the following sentence:

Don’t make the play that’s best for the current turn, try to find the move that’s best for the game.

If you’re trying to improve as a Magic player, planning ahead and developing a sight for the future is quite possibly the most important skill you can cultivate.

Matti Kuisma (Twitter)