Predicting the Future

In 2003, Sports Illustrated magazine ranked the worst draft flops in NBA history. At the top of the list were two names, LaRue Martin and Sam Bowie, both of whom were picked by Stu Inman of the Portland Trail Blazers.

Stu Inman (Quated from Wikipedia)

In the 1972 draft, the Trail Blazers had the first pick of the whole draft and chose LaRue Martin over eventual Hall of Famers Bob McAdoo and Julius “Dr. J” Erving. Martin’s career was a complete bust, and he scored less points in his whole career than McAdoo did in his rookie season alone. Julius Erving, the 12th pick, became a sixteen-time All-Star and one of the top scorers in the history of professional basketball.

The 1984 draft where Inman took Sam Bowie as the second pick of the draft was possibly even worse. Bowie’s career was full of injuries that broke up his seasons so he was never able to realize his potential as Portland’s center. However, if you’re a basketball fan, you probably recognize some of the other players taken in that draft: Hall of Famers Charles Barkley and John Stockton. And even if you don’t follow basketball at all, you have still heard of the player taken right after Bowie. His name is Michael Jordan.

I have a question for you though:

Were the outcomes of those picks due to bad luck or bad decision-making?

The thing is, predicting the trajectories of young athletes is incredibly hard. When analyzing college quarterbacks drafted into the NFL, economists Berri & Simmons found no connection between how highly the player was drafted and how well they actually did in the professional level games. Tom Brady, possibly the greatest quarterback ever to play American football, was grabbed as the 199th pick of the draft.

One of the problems in both talent scouting and Magic is that your decisions and their outcomes don’t have a 1-to-1 correlation. If you win, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you played well, and if you lose, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you made a mistake. Judging the quality of the decision solely by the outcome is often harmful. When looking at individual cases, the results of bad decision-making and bad luck are often indistinguishable from each other – and the same goes for good decisions and good luck.

Now, compare this to mana screw in Magic. Whenever you look at an individual game where you lose to it, it’s always going to seem like bad luck. And no matter how good you are or how optimal your lands-to-spells ratio is, you will still sometimes suffer from having too few lands. The outcome itself doesn’t tell you much.

But the frequency does.

Despite of the two picks mentioned earlier, Stu Inman was held in high regard as a talent scout. Norm Sonju, co-founder of the Dallas Mavericks basketball team, says that Stu was “considered a genius” and many viewed him as “the best personnel man in the league”.

If you’ve ever seen a professional Magic player draft a great deck from cards that you thought were underwhelming, Stu Inman did the same in basketball. Just like team MTGMintCard dominated Amonkhet drafts by wheeling 《Slither Blade》s for their hyper aggressive decks, Inman built the 1977 NBA championship team with half of the top scorers of the team being late picks from 2nd and 3rd rounds of draft.

One of the reasons why the Trail Blazers didn’t pick Michael Jordan in ‘84 was that they had already managed to steal an incredible player with a very similar skill set in the previous year’s draft. As the 14th pick of the ‘83 draft, Inman grabbed Clyde “The Glide” Drexler, a shooting guard who other teams thought couldn’t shoot. But Inman saw Drexler’s work ethic and potential, and the shooter who couldn’t shoot eventually built a Hall of Fame-worthy career of over 22,000 points, 6 000 rebounds and 6,000 assists.

Inman’s value as a talent scout wasn’t defined by any single draft pick, good or bad. It was defined by the frequency at which he was able to find undervalued players and help them become better than they were before.

Similarly in Magic, by making good decisions you will lose to bad luck less often. Good decisions won’t change the outcomes, but they will change the frequency. An individual mana screw is always going to be a tragedy, but if you look at millions of mana screws, they become a statistic you can alter.

What I’m trying to do in this article is to explain how to manipulate the mathematics and beat bad luck as often as possible. It’s easier to take calculated risks when you understand where the numbers come from.

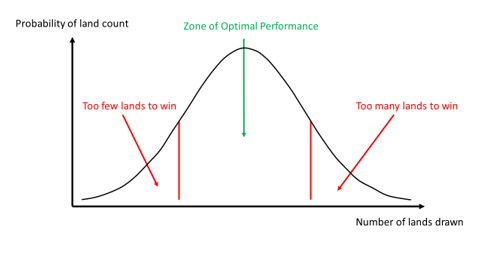

Zone of Optimal Performance

Most of you probably agree that the simplest way of getting unlucky is drawing either too few or too many lands. But let me ask you this:

How many lands are too few? How many lands are too many?

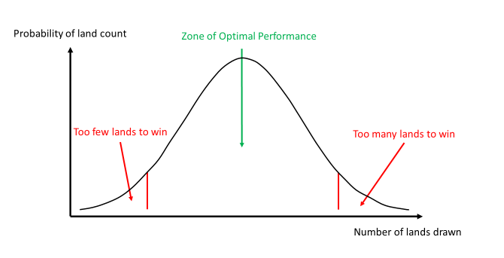

Regardless of how long the game has been, the graph will look something like this:

Graph 1

Now, what if you could change it to look like this?

Graph 2

That’s what I’m talking about when I’m talking about beating bad luck. When you start thinking about it, there are actually a lot of things you can do to help your deck become more like the one in graph 2. In my experience, the vast majority of players don’t consider these limits anywhere near enough – if they do so at all.

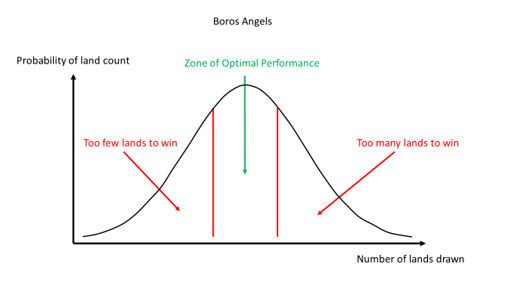

For many decks that have been popular over the years, like Boros Angels, the graph looks something like this:

Graph 3: Boros Angels

When they work, they often work wonderfully, curving out with powerful threats followed by more powerful threats, but they have a very narrow Zone of Optimal Performance. A typical match against Boros Angels is that one game they lose to stumbling a bit on lands, one they win by curving out, and the last one they lose to flooding. They can’t afford to miss land drops, but they don’t really have any flood protection either.

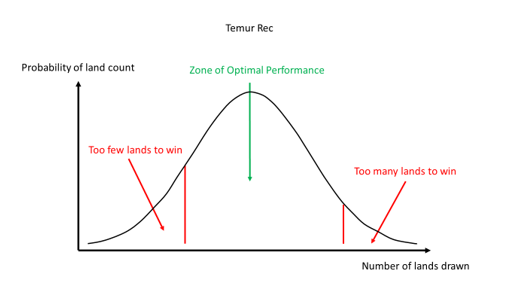

Compare that to a successful deck like Temur Reclamation, which dominated pre-M21 Standard. Now, I will admit that Rec doesn’t actually function well with few lands, but it solves that problem by playing a ton of them, usually 28 or 29. Most decks can’t afford to play that many because it would lead to the reverse problem, flooding, but Rec is great at mitigating that part.

If you look at the Temur Reclamation mana base, a third of its lands can turn into pseudo spells. Many lists run 3 《Castle Vantress》, 4 《Ketria Triome》 and 2 《Blast Zone》, which more or less count as action if you need them to. It’s quite a bit easier to have an optimal ratio of lands and spells when you have 9 Land//Spell split cards in your deck.

Graph 4: Temur Reclamation

You can achieve this same effect by playing cheap card selection. One of the most important functions of 《Brainstorm》s and 《Ponder》s in Legacy is ensuring that you have an optimal mix of cards, and they take the blue decks to a level of consistency that Boros Angels can only dream of. There’s a reason why 《Ponder》 and 《Preordain》 are banned in Modern.

This is also why the best decks in any given format often feel like they win more than they should even in “bad” matchups. They are simply more consistent than the rest. Take a deck like Modern Izzet Phoenix in the spring of 2019. When I was testing against it, I was consistently winning less than I thought I should. If both decks drew optimally, I often felt like my cards aligned well against theirs. But the Zone of Optimal Performance was wider for the Phoenix deck than it was for almost any other deck in the format.

Card Advantage

One of the best ways to beat bad luck is by playing card advantage. Not only does it help with flooding, it also helps with mulligans. This is especially important in Limited, where cards often trade 1-for-1 and thus raw card quantity is more important than in Constructed. Let’s say that you draw 7 lands and 3 spells, and your opponent draws 5 lands and 5 spells. If all of your spells trade 1-for-1, you’re in trouble, but every 2-for-1 you draw means you can afford to draw less spells and still be in the game. Card advantage is at its best when you have the least resources and need the most help.

I know it’s not exactly groundbreaking to say that card advantage is good, but I’m pretty sure that the most players still underestimate HOW important it is, especially in slow Sealed formats. Theros Beyond Death is a good example of this. As I learned more about the format and realized how grindy the games tend to be, I was more and more willing to include even weaker sources of card advantage and splashed them more liberally than I would have in other formats.

Particularly valuable are card advantage engines that produce a continuous stream of value – something like a 《Shimmerwing Chimera》 paired with an 《Omen of the Sea》, or most planeswalkers. When you ask yourself “How many opposing cards can this trade with?” there isn’t really an upper limit to the answer. One of my opponents in the recent Mythic Invitational Qualifier conceded after I went turn 2 《Growth Spiral》 into turn 3 《Nightpack Ambusher》, as they knew that they wouldn’t be able to beat the steady supply of Wolf tokens. Effects like this dramatically shift the limit of “Too many lands to win” upwards.

Scalability

Scalability is a concept closely related to both operating on various land counts and card advantage. It essentially describes how good individual cards are with varying amounts of mana available – that is, how well they “scale”.

Let’s start with low-end scalability. This is a Sealed deck that I used to make the top 8 of a Magic Online tournament earlier this year:

- Matti Kuisma

- – UB

- Magic Online Limited Super Qualifier

- (Top8)

8 《Island》

-Land (17)- 1 《Devourer of Memory》

1 《Lampad of Death’s Vigil》

1 《Tymaret, Chosen from Death》

1 《Nadir Kraken》

1 《Scavenging Harpy》

1 《Vexing Gull》

1 《Shimmerwing Chimera》

1 《Rage-Scarred Berserker》

1 《Witness of Tomorrows》

-Creature (9)-

1 《Pharika’s Libation》

1 《Memory Drain》

4 《Mire’s Grasp》

1 《Omen of the Dead》

1 《Omen of the Sea》

2 《Elspeth’s Nightmare》

2 《Ichthyomorphosis》

1 《Ashiok, Nightmare Muse》

-Spell (14)-

An important reason why I thought this deck was the best one I had had in that Sealed format was that it operated well on just a few lands. I was able to win multiple games where I missed a lot of land drops and most other decks would’ve lost. The key to low-end scalability is playing cheap cards that can trade for more expensive cards, like 《Mire’s Grasp》, 《Swords to Plowshares》 or even 《Riptide Turtle》. When building a Sealed pool, you should look for cards that let you survive even if you stumble.

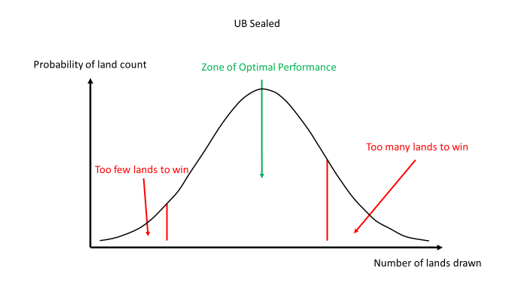

For this deck, the graph looked something like this:

Graph 5

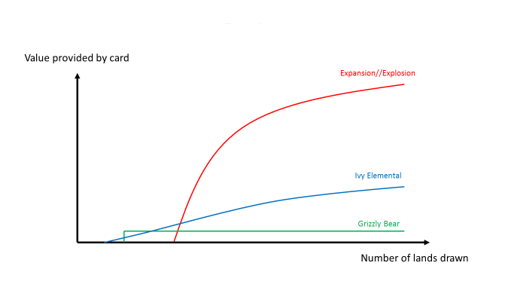

The next thing to be on the lookout for is scalability in the high end. If you look at a card like 《Ivy Elemental》, the rate on it is kind of bad regardless of how much mana you cast it for. Yet it’s still a good card in Limited because of scalability – and gets a bit of extra flavour in Ikoria by working well with Mutate cards. There are a ton of mechanics in Magic’s history that offer scalability in some way: kicker, adventure, entwine, flashback and so on.

Scalability is probably the most important reason why Temur Reclamation has been such a dominant force in pre-M21 Standard. The combination of 《Wilderness Reclamation》 and 《Expansion/Explosion》 provides an easy way to go over the top of any other deck in the format.

They even scale well fine if you draw them separately. When you’re stuck on 4 mana, 《Reclamation》 gives you a significant mana boost and 《Expansion》 can act as a removal spell by copying an 《Aether Gust》 or a 《Scorching Dragonfire》. If you’re flooded, 《Reclamation》 lets you churn through your deck with a 《Castle Vantress》 and pumps up huge Shark tokens. 《Explosion》 is also good by itself, as it draws you a bunch of cards even if you don’t have 《Reclamation》 to turbo charge it.

Graph 6

The one time in recent years when I decided to play a Red-White Midrange deck in a tournament was after Guilds of Ravnica came out. The most popular deck at the time was BG Midrange, and my brew tried to take advantage of it by playing threats that couldn’t be efficiently removed: 《Adanto Vanguard》, 《History of Benalia》 and 《Rekindling Phoenix》. One of the key pieces of the deck was a full FOUR copies 《Banefire》 in the main deck, specifically as a source of scalability that these kinds of decks usually lack.

The games against BG sometimes went long, and the RW deck needed a way to close them out – a role which 《Banefire》 played admirably, while also being a serviceable removal spell against some cheaper creatures earlier in the game. The concept of playing scalable cards in Red-White was so unthinkable to one of my opponents that he decided to call a judge to check my decklist. He couldn’t believe that I had multiple 《Banefire》s in the main deck!

I think this is an example of a deckbuilding decision that very few people would’ve made, but which was a critical piece for the deck. I’m not claiming that 《Banefire》 is a great card, but it did serve an important role in the deck, especially against control decks which were its worst matchups.

That said, it still would’ve been better for me to just play the best deck. It was the classic situation where even though I believe I was favoured against BG Midrange, I could’ve gotten the same edge by having a good BG list for the mirror match, while being better off against the rest of the field. One of the defining features of that deck was that 《Merfolk Branchwalker》 and 《Jadelight Ranger》 made it easy to hit your land drops early in the game, while digging towards strong action spells later. In other words, it was able to stretch the Zone of Optimal Performance wider than the rest of the format.

Robustness

Next up I have two more questions:

How many things can go wrong with your deck? How detrimental is it when they do?

Let’s look at two mana bases as examples:

Sample 1

Sample 2

Which one of these is a better mana base? In some ways, they are very similar: each one has 14 sources of each color. However, if you look at it from the perspective of “How many things can go wrong?” it is clear that the first mana base is superior to the second one.

First of all, the additional color is one more thing that you can miss. Let’s say that the probability of missing a land of a certain color is X. Even though that probability stays the same across each color, that’s not the number you should be interested in. The number that matters is having ALL of your colors, the probability for which is roughly (1-x)^2 for a two color deck and (1-x)^3 for a three color deck.

Using the mana bases above, I calculated the probabilities to have at least one source of each color in your 7 card opening hand with no more than 5 lands to be about 73% and 65% respectively. That’s a significant difference in favor of the 2-color variant.

Second, the 3-color base is more prone to having awkward lands. If your three lands are 2 《Forest》s and 1 《Hallowed Fountain》, you technically have a source of each color but it doesn’t mean that you can cast all of your spells. That combination doesn’t, for example, cast a spell like 《Teferi, Time Raveler》. Another thing that can go wrong is drawing only checklands like 《Glacial Fortress》 and 《Hinterland Harbor》. If all of your lands come into play tapped, you’re gonna have a lot of catching up to do.

“How many things can go wrong?” isn’t only about mana bases, it also covers gameplay aspects like“what if you draw an uneven mix of ramp spells and payoffs?” and “what if you draw the wrong half of your deck?”

As much as it pains me to admit it, Dredge is actually a great example of a deck that has a lot of things that can go wrong, especially in opening hands. Generally speaking, your opening hand requires 2 lands, a discard outlet, and a dredger to get going. If any one of these is missing, the hand is probably bad. Not only that, but it has a lot of cards that are actively harmful to have in your hand. For example, an opening hand with 3 《Narcomoeba》s is garbage even if it has all the necessary pieces.

And even if your opening hand does have all the right ingredients, you’re still just rolling a dice on your dredges. You need to both hit more dredgers to keep your dredge chain going AND actually hit the payoffs as well. And not just any payoffs – if you only hit 《Prized Amalgam》s you’re not going to get very far, 《Bloodghast》s are useless if you don’t have a land drop to bring them back, and if you hit only 《Narcomoeba》s your clock is probably going to be too slow.

That brings us to “how detrimental is it if things DO go wrong?” The saving grace for Dredge is that having to mulligan an opening hand is not much of a cost. In fact, the first mulligan is often a benefit, because it lets you put a payoff card back into the deck. Dredge can easily go down to 4 or sometimes even 3 cards to dig for the cards it needs and still win – having the right cards is much more important than having many of them.

On the other hand, we have one-card decks like 《Winota, Joiner of Forces》, which more or less can’t win without their namesake piece. With 《Winota, Joiner of Forces》 in particular I don’t think you should be allowed to complain about bad luck. All you are doing with that deck is playing the percentages. It’s not bad luck to not find a 《Winota, Joiner of Forces》 after casting an 《Adventurous Impulse》 and a 《Silhana Wayfinder》, and it’s not bad luck to not hit an 《Agent of Treachery》 from three 《Winota, Joiner of Forces》 triggers and then get 《Shatter the Sky》’d out of the game. It’s not bad luck if your deck folds completely to a single removal spell like 《Justice Strike》 or 《Heartless Act》.

If your deck is built so that it can’t win without drawing a certain card, having enough support for it, having that card stick AND hitting the payoff cards from it instead of drawing them naturally, it is going to cap your win percentage. It is INEVITABLE to have games where one or more of those things go wrong. It is a choice you made when you built the deck. The 《Winota, Joiner of Forces》 deck was very powerful when it worked, but it was also very, very fragile.

Robustness is another important factor which makes Temur Reclamation such a great deck. It isn’t reliant on any single card, has multiple threats capable of winning the game, those threats are hard to deal with effectively, and most of its cards are good by themselves and against everybody so it’s hard to draw the wrong half of your deck or a bad mix of those cards.

Recap

Whether you’re drafting, building a Sealed pool or trying to break a Constructed format, here’s a checklist for making your deck more resilient to variance:

Note that there aren’t always ways to overcome these obstacles, especially in small formats. Sometimes the solution is simply to understand that a deck like Temur Reclamation is better at these things than a deck like Boros Angels, and you should just play the better deck. These are, in my opinion, some of the best metrics for trying to figure out which decks are in fact the better ones.

-Matti (Twitter)