Introduction

With falling off the train, working again, and the state of organized play, I haven’t played Magic in over 2 months now. Taking a step back when I’m at the top of my game is bittersweet, but such is life. I’ll be back soon, I’m sure. It’s hard to quit Magic for long.

Even so, I still have some articles I’d like to write. I have no opinions on standard or historic, and you shouldn’t trust any opinions I had. But I’d like to continue thinking about my breakthroughs over the past two years and sharing what lessons I can. If you’re still dreaming the Pro Tour dream, I hope I can make your journey easier than mine was.

The Great Tao

Magic is deep and multifaceted. The bulk of competitive theory focuses on navigating games, but Magic has so many other aspects. There’s deck selection, card evaluation, metagame prediction, sideboard construction, information processing – Magic has too many subgames to list. Brian Braun-Duin has an excellent article on the topic.

Between all these subgames, everyone has strengths and weaknesses. Of course, an experienced player will be more capable across the board than a beginner. But even with a big skill gap between two competitive players, the weaker player will often have greater expertise in some area than the stronger one. And with similarly skilled players, even players at the top of the game, the imbalances are myriad and extreme.

The most common advice on improving at Magic is to play against stronger players. That’s certainly the smoothest path. It’s hard not to learn from players who are better at everything than you are. However, working with players that much better than you typically isn’t an option, because there’s nothing you can teach them. If you happen to know LSV from high school, you can skip the line. But for everyone else, the real gains are in teaching and learning from your peers.

Paying closer attention to how other players approached the game, particularly players I’d previously dismissed as weaker than myself, was a paradigm shift for me. Almost everyone you meet represents an opportunity to learn. The real work of learning is discovering what they can teach you.

My personal strength has always been playing games – strategizing, technical play, reading hands. Because the lower levels of tournament Magic disproportionately reward good play, I found success there despite my weaknesses, which in turn led to an inflated sense of my abilities. But when I started playing Pro Tours, those weaknesses showed. I started losing more, and I couldn’t explain why.

When I really started paying attention to other players, I noticed not just subtle flaws in my strengths, but entire concepts I’d never considered before. For example, for deck selection, I’d always aimed to identify and play the best deck. The notion of explicitly predicting a metagame and choosing or constructing a deck to beat it was foreign to me. When I recognized this gap, learning was as easy as watching.

Before the paradigm shift, when I saw sloppy play, I’d dismiss the player. After, I’d pay particular attention to players who succeeded despite weak technical play or incomplete theoretical understandings. Almost always, these players excelled at one or more subgames I’d completely ignored.

As with everything, balance is key. You need enough conviction to question others and defend your beliefs, but enough humility to adopt new frameworks. Personally, when I’ve directly tried a strategy or deck or technique, I’m firm in my conclusions, but I never dismiss an idea out of hand and I’ll try anything once.

Avengers, Assemble!

The ideal testing team would be one person responsible for each aspect of tournament preparation, like a heist crew. You’d want a brewer, a leader, a pair of testers, a data analyst, and so on. In practice, players aren’t quite that specialized, and it’s good for everyone to touch every part of the testing process anyway.

More perspectives is better, and everyone ultimately needs to patch their leaks. Still, if you’re organizing a team, you should select people from that perspective. A balanced mix of strengths and weaknesses is more important than the overall skill level of each player.

In competitive Magic, like in Magic theory, there’s far too much focus on in-game play. A team of premier pilots who can’t build decks, predict metagames, or organize testing is self-evidently dysfunctional. Playing games well helps generate data, figure out matchups, and formulate sideboard plans, but it’s a minor art in the overall scheme of tournament preparation.

When you’re looking to join a team, instead of asking what you stand to gain, ask what you stand to contribute. If you join a team where your skills are redundant, you’ll have less responsibility, feel less comfortable contributing, and ultimately add less. You won’t learn as much and may leave a bad impression. You may have a better deck for one tournament, but may not even improve your chances of succeeding because you’ll have been so removed from the process.

Radical Candor

In practice, of course, it’s hard to get a sense for someone’s strengths and weaknesses before working with them. For the most part, this problem has two solutions. The first is to work only with people you know well, so you can manually balance everyone’s affinities ahead of time. Most notable Magic teams use some form of this approach, but it has the major cost of overlooking new talent. Professional Magic is notorious for its insularity, and this dynamic is big part of that reputation. The second, which was the inspiration for Team 7%, is optimism under uncertainty.

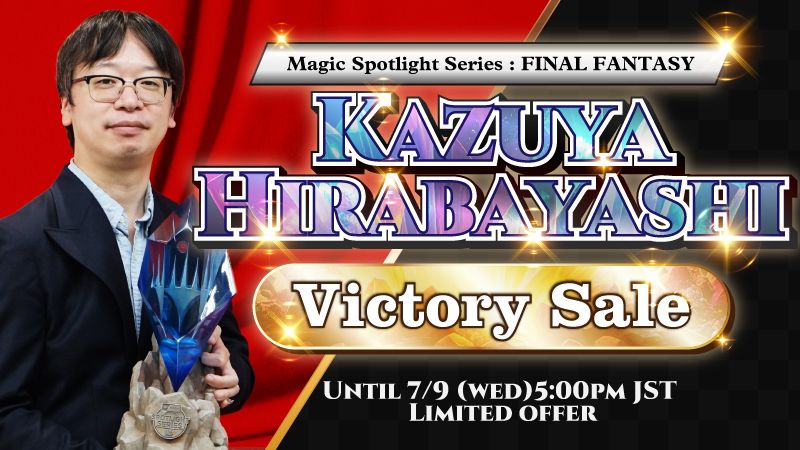

The name Team 7% originated as a joke after Jacob Nagro noticed that our team was a full 5% of Pro Tour Richmond. The team grew even bigger after that, such that we were 7% of the Regional Pro Tour in Phoenix. One of our underlying principles was that when someone asked to work with us, our default policy was accepting them. We only declined when the existing group had specific objections. The group was ultimately large enough that we had specialists in every key role even though we didn’t explicitly seek them out. Not every new add worked out, but the global cost of a mistaken add is lower than the gain from a good one.

Granted, operating such a big group has unique complications. Team 7% needed clearer processes, stricter organization, and closer “management” than traditional testing teams. We were lucky that many of the original members of the group were older and further in their careers and could help establish the team culture.

Tim Wu, for example, is an actual manager at the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Our systems weren’t perfect, of course, but they didn’t buckle under over 20 people. You can find our team guidelines here. We haven’t revised them since the onset of the pandemic so the details are dated, but the core concepts stand.

The biggest flaw in our process was that some people got lost in the cracks. Note I advised you above not to join a team unless you thought you could contribute to it. Conversely, we added a number of people who couldn’t or weren’t ready to properly contribute, and they all eventually fell away.

From the system’s perspective, these were expected losses. But for the individuals, they probably didn’t have a great experience and may even have been better served working on their own. We should have had clearer expectations for new adds and explicitly defined policies for phasing out members.

And maybe the organizational psychology books I’ve been reading have pureed my brain, but I see Team 7% as one of the most ambitious and successful projects in the past decade of competitive Magic. It discovered and supported almost all the emerging American talent of the past couple years, including myself.

Players Tour Phoenix 2020 Champion: Corey Burkhart

Image Copyright: MAGIC ESPORTS

At the Regional Pro Tour in Phoenix, we were 7% of the starting field, 50% off the top 8, and ultimately took the trophy. We missed the top cut at the Zendikar Rising Championship, but still put Gavin Thompson into the Rivals Gauntlet and earned David Inglis and Jonny Guttman qualifications.

I’ve stepped back from the process with my break from Magic, but I understand that Austin, David, and Jonny are keeping the 7% spirit alive. I’m excited to cheer them on and hope they continue changing the paradigm.

Two Young Fish Swimming Along

Networking was and is a weakness for me. Looking back, I got very lucky to make the connections in Magic that I did. I started playing Pro Tours before Grand Prix, qualifying through Magic Online, so I was entirely detached from the professional community.

Phil Silberman, who I knew from my LGS in Chicago, recommended me cold to Thien Nguyen for my third Pro Tour in Sydney. Thien introduced me to Nathan Smith, who connected me to most of the people I ultimately met in competitive Magic.

Similarly, I first met Jacob Nagro playing PPTQs in New Mexico. We were both complete unknowns at the time. I’d just played my first Pro Tour, and Jacob had yet to qualify. He was a pleasant opponent and beat me badly in both PPTQs.

After we played at his first Pro Tour in Honolulu, where he beat me again, I invited him to dinner with Nathan and the rest of our group based on my impressions from those PPTQs. We wound up working together for every other Pro Tour we both played, and he’s one of the players I’ve learned the most from.

The main thing I’ve learned here, following the theme of the article, is optimism under uncertainty. If you’re humble, helpful, and capable, people will want to meet you. If you’re an asshole, the competitive community has a longer and more precise memory than you can imagine. If cooperation and humility are not your default settings, it’s on you to reprogram yourself.

Conclusion

Yield and overcome. Bend and be straight. Empty and be full. Wear out and be new. Have little and gain. Have much and be confused. Be truly whole, and all things will come to you.

This is my favorite mantra from the Tao Te Ching, and I’ve taken it to heart in improving at Magic and in life since reading it. Like many passages in the Tao Te Ching, every phrase in it is a contradiction. How can someone both yield and overcome? If someone is truly whole, what could she want?

But more importantly, why yield? And why overcome? There will always be arguments for and against both approaches in any situation. Similarly, there will always be costs and benefits to conviction, and to humility. The key to success, or at least peace, is finding the balance between extremes. That’s easier said than done, of course. Personally, I need to constantly work to find and hold the center.

I hope these ideas will prove useful to you. If you agree with them, see if you can find disagreements. If you disagree, try to find lessons you can take from them still.

Until next time, best of luck.

Allen Wu (Twitter)