Introduction

For this article, I decided to do something a little different and possibly controversial. I decided to tell you what I think makes a magic player successful, or not. And it is neither skill, nor luck. In a nutshell, I am going to tell you that you are a great player who plays real poorly, that you probably do not need to play against stronger players, and that getting much better results is mostly about making sure you are absolutely exhausted by the end of a tournament. Still interested? Let’s go!

To puzzle or not to puzzle? |

Magic is often perceived as a game of puzzles, at least for the in-game part (as opposed to deck construction), every now and then you encounter a tough situation where it is clear that there is a right choice to be made, but the right choice is not immediately obvious. If you get it right, your win percentage goes up, and if not, well, you lose more.

This is only half-true, and I think it leads to one of the biggest misunderstandings that stops reasonably gifted players from getting to the next level. Half-true, because yes, Magic can be seen as a succession of puzzles. Half-wrong, because the correlation between how good you are at Magic and how good you are at solving those puzzles is actually very small, it is not really about how well you solve the puzzles, it is instead about how many of these puzzles you can see. Let me show you why, and how to use that as a way to grow as a Magic player.

What is a typical puzzle?Example 1

|

This is from one of my games in preparation for GP Madrid, and it was a pretty exciting one. Here, I am controlling Jaberwocki’s turn and want to do as much damage as possible to stop him from recouping. How do I do that?

This is the typical example of a puzzle you’d see in an online article, or that you would remember from a game you played. It is obviously a little complex, it looks critical since the game is close to an end, and there is a clear right, straightforward answer to be found.

Here, it is fairly obvious that you want to wipe your opponent’s board, and make sure you leave him with as little energy as possible so he cannot use his Aetherwork Marvel for some time. Simply attacking with Ishkanah and playing 《Kozilek's Return》 is underwhelming, because you would leave him with a Chandra on one and 4 energies, i.e a dangerous combination. So you need to play Marvel and activate it (missing or hurting him more) and end up with as little energy as possible. The best sequencing I found was minus Chandra on Ishkanah, attack into Emrakul, and post-combat play Marvel and 《Kozilek's Return》 while spending energy with both 《Aether Hub》 and 《Servant of the Conduit》, ending up with exactly 0 energy after the Marvel activation. For the record, I still lost this game in a very exciting fashion, but that is not really the point. The point is there was a clear solution to the puzzle, and it was easy to notice you had to find it.

So, cool, we got that out of the way. You must be thinking that it was not super hard, let alone relevant. And you are right, because solving this is not the reason why some players win more than others. See, there are three issues of comparable importance if you think solving that kind puzzles are what makes a player good or bad:

1. Solving puzzles is either not very hard, or not very important

I actually think that a decent portion of you might be better at solving intricated puzzles than Owen (or any pro, really. I just take Owen as an example since he is, you know, really really good). But in 95% of the cases, it will not make any difference. See, the puzzles that you see in articles are always like the one I showed you, i.e mechanical. For that reason, most of the time there are a small number of course of actions that you might take, and “computing” all of them is decently easy so, if you give it some thought, you will find the right solution. In a smaller number of cases, the best course of action is very hard to identify, but that is only because the difference between the best play and the second-best play is super thin. See this tweet from Raphael Levy, for example:

Ur upkeep, u untap Key to the City, 5 lands in play. 12 lands / 26 cards in ur deck, 1 card at 4 mana that wins the game (or u're dead).

— Raphael Levy (@hahamoud) 2016年11月24日

The situation is interesting as far as a brain teaser goes, and the results of the poll show how hard it was for someone to find the correct answer. Guess why? Because there is almost no difference. I ran the numbers on this and the best choice is to not draw, giving you a 3,85% chance to win. If you elected to draw, you went down to 3,69%. In this occurrence, being better at solving puzzles would result in a 0,16% increase in your win percentage for a situation that will happen about once every hundred games or so (I mean, a situation where it is that hard to determine the best play even though you have all the information and is trying to find the best play). Also, I am certain that many amateur magic players with a degree in mathematics would be better at solving it than most pros.

2. If a puzzle is interesting to solve, it is probably not an important puzzle

Almost every article that lets you solve a puzzle has a huge bias in how they select the puzzle. In order to be decisive, exhaustive and relatively short, the article has to be about a puzzle with a clear cut answer, and where most of the data is on the board. The example I gave above is representative of that bias, there is a limited number of options, and the unknown information consists of a single draw step. This would let me give you a solution that I can demonstrate to be 100% correct without having to go through tons and tons of options and branches of probability. Also, I made sure to select a situation that is extremely short-term, since it basically comes down to “win or lose next turn”. This is how I keep things clear, simple and exciting with the whole thing being quite boring if you had the same kind of scenario, except the best play would get your opponent to 17 and the second-best play got him to 19.

But that does not mean that this puzzle would be of less consequence, it just means that it would be harder to solve and explain. In order to make myself perfectly clear, let me draw a parallel with chess:

Problem No. 1: Black is to play, what is the best move?

This is an exciting position if you like chess. Black is super far ahead, because they can straight-up win the game with QueenE3 takes BishopG1, TowerB1 takes Queen G1, KnightG4 goes to F2, checkmate. Any one remotely interested in chess would take a moment to try and solve this, because it is very clear that there is something to find and that they might find it. Any decent player will actually find it in a fairly short amount of time.

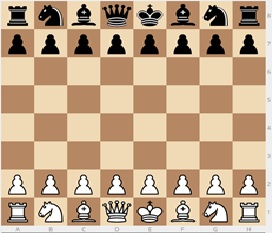

Problem No. 2: White is to play, what is the best move?

This is not an exciting position: it is the starting position. Anyone would consider this problem a joke, since it is just so hard to solve. Common opinion is that 1.E4, 1.D4, and to a lesser extent 1.C4 or even 1.Knight F3 (the Reti opening) are the best options, but as of now no one can claim to have a definite answer.

Now, what do you think is more important? Being able to figure out what to do in situation 1, that will happen once in your life (a bit more once you learn to recognize the pattern, but whatever), or in situation 2, that happens every single time by definition? The answer is situation 2, because if you get smashed in the opening, you are very unlikely to ever to a position where you can find a miracle combination to save your life. If you wait until a clear puzzle presents to you, then there is a good chance that it is way too late. Every time I attend a local event, like a prerelease, I see the same mistake: my opponent plays at blazing speed turns one to five or six, finds himself in a losing position, and play agonizingly slow for the last few turns. Often enough, they will find very smart lines of play, try to bluff me, and basically elevate their level a lot. But it is just too late, not doing the correct plays in the early stages of the game has dug them too far into a hole, and there is no coming out.

In other words, this is the kind of puzzle you should be working on:

|  |  |  |

|  |  |

This is your starting hand game 1 against an unknown opponent, with you on the play. What is the optimal play?

Here, there are a lot more moving parts than in a typical article puzzle. It is not even clear what the question is. But all in all, I think being able to figure out what you should do “in the abstract” ( meaning when you cannot calculate with certainty the impact of your choice) is going to help step up your game way more that of computing a clear, determinative line of play from start to end. Since it is obviously impossible to solve this abstract puzzle through sheer computation, because the computation would have to run over the course of a whole game, you need to resort to tried and true generic play strategy.

If we only focus on your first land here, you have to find out which is better between 《Hissing Quagmire》 and 《Evolving Wilds》. I am certain than 99%, you would not spend more than 5 seconds deciding, while you could spend as long as a minute on example 1 if it happened in a game. Which is weird, because example 2 is both more complex to solve, and more useful to solve as it will require the kind of strategic thinking you can re-use in future game (whereas example 1 is a one-time thing where all you need is specific calculations).

|  |

Playing 《Hissing Quagmire》 is the most intuitive play here. First, it is “the better land” since it lets you cast 《Grasp of Darkness》 on turn 2 if you draw it, or cast 《Grim Flayer》, while 《Evolving Wilds》 forces you to choose. It also lets you save that 《Evolving Wilds》 in case you would draw a 《Tireless Tracker》, potentially netting you another clue. Finally, since you are likely to not play the other untap land until turn 5 (since your hand curves out really well so far), opening with 《Hissing Quagmire》 means that if your opponent was to play RG Marvel and open with 《Servant of the Conduit》 into 《Chandra, Torch of Defiance》 killing your 《Grim Flayer》, you could instantly destroy his planeswalker with your manland.

Still, opening with 《Evolving Wilds》 has a few hidden bonuses that would be worth considering given the right match-up. The first one is getting to delirium more reliably: if you get your ideal draw of 《Grim Flayer》 into Liliana into 《Mindwrack Demon》, the main way you’ll lose is by missing delirium. Having a guaranteed land in your graveyard would help a lot in that regard. You should also consider the fact that you might not hit another untap land in your first two draws, and have to cast 《Grapple with the Past》 on turn 3. In that specific scenario, you would be much better off starting with 《Evolving Wilds》: not only does it gives you a better chance of getting your 《Grim Flayer》 to 4/4, which is often the difference between connecting or not, but it most importantly guarantees that your 《Grapple with the Past》 will not fizzle, which would be a small disaster. It poses the issue that drawing a 《Forest》 would not let you cast Liliana on turn 3, though.

|  |  |

All in all, and given that I think I would rather cast 《Grim Flayer》 on turn 2 than 《Grasp of Darkness》 in almost every scenario, I think I would sometimes go with the safer, yet counter-intuitive play of 《Evolving Wilds》 depending on what match-up I expect. But that is not the point at all: what I wanted to emphasize is that your decision could easily be game-changing, and isn’t at all obvious (you will not solve this in a single tweet!), and is well worth a puzzle.

3. It is not about how well you solve the puzzle, it is about how many puzzles you can solve

Now, let us be honest. In a typical game, how long would you spend thinking about example 2, compared to example 1? I think most of you will say something like “a little bit less”. This is already wrong, because example 2 is at least as important, more complex, and figuring it out will give you reusable material for the future (which, in the long run, amounts to a better understanding of the game). But the actual answer is probably closer to “I almost do not think about example 2”. Why? Because puzzles like example 2 happen all the time, maybe five or six times per game, while example 1 only happens occasionally. You just do not notice it. And this is the most important thing to consider if you want to improve: you are already good at solving puzzles, but you are probably terrible at noticing them. Owen might be 1% better than you at solving most puzzles, or maybe 10% cause he is really good, but that is not where he has you beaten. He beats you because he sees 95% of the puzzles, when you only notice 5%. Which means that every turn, he will find the right solution (or at least try to) to a puzzle you did not even consider.

|  |  |

You might call it “playing in automatic mode”. You might call it “intellectual laziness”. You might call it “focus”, or even “perfectionism”. All those terms apply, but they reduce the problem to something you could just change by trying harder. That is very wrong. Being able to try and see all the hidden puzzles is draining, and it takes at as much energy and skill as solving them. Hell, after a certain level, I would even say that noticing the puzzles is the most important skill of all, because any competitive magic player (which I assume you are) will solve most of them anyway. If you are not convinced, please try to think of all the players who are better than you: do you really think they are all smarter? Did not you ever notice than player X does not think quite as fast as you, “has a weaker CPU” if you allow me, but still wins much more than you do? This is probably why. Even though he cannot spend as much brain power in a given situation, he will still outperform you because he spends that limited amount of brainpower on many more occasions than you do.

As you can probably tell, this is a subject that is very dear to my heart. I wish I could make you feel how important this is, and the pivotal moment in my Magic “career” has been the day I realized that I was able to solve about every puzzle my friend showed me about their games in no time, but could never tell them about my own puzzles because I just never bothered to notice then. For the record, that was Grand Prix Prague 2013, a month before my first PT top8 in Dublin. So if I could give you just one advice: every time you are about to make a play, try to spot the puzzle behind it. There is always one, and looking for it is the most relevant thing you can do if you want to become a better player.

Until next time,

Pierre Dagen

Cards found in the Article

Share in Twitter

Share in Facebook

Pierre Dagen

Pierre Dagen

One of Europe’s most well-recognized players, whom at Pro Tour: Theros squared off against his “Les Bleus” teammate Jeremy Dezani in a Mono-Blue Devotion mirror match in the finals, a game to go down in magic history. Other notable achievements include a second PT top8 in Honolulu 2016, 3 GP Top 8’s, and 3rd place at the World Magic Cup 2015 as captain of the French team.

Related Articles

- 2016/11/27

- Analyzing Past Tournaments

- Lukas Blohon